Every state is looking for ways to reduce its Medicaid spending. Here’s an untested idea: integrate existing technology to help Medicaid beneficiaries and their health care providers monitor and manage their health care.

Medicaid’s Scope

The federal-state Medicaid program is by far the largest health insurance plan, covering 62 million Americans, and it is the first or second biggest budget item in most states. Actually, Medicaid is three different programs.

- It provides health insurance for low-income children, pregnant women and some adults, covering about 40 percent of all births, and more than 50 percent in some states;

-

It is the primary source of coverage for the disabled; and

-

It covers certain costs for poor seniors, including nursing home care and the premiums and out-of-pocket costs not covered by Medicare.

While low-income children, pregnant women and adults account for 75 percent of total beneficiaries, they only spend 34 percent of Medicaid funds. The disabled, by contrast, are 15 percent of the Medicaid population but account for 42 percent of expenditures.

Medicaid Populations Face Many Challenges

Medicaid populations have lower education levels and tend to work in hourly jobs that do not let them take off without clocking out. Yet most clinics and doctors’ offices are open during business hours, which means seeing a doctor in an ambulatory setting likely costs Medicaid beneficiaries income—income they may not be able to lose. That’s one reason why low-income families tend not to establish doctor-patient relationships with a family doctor, opting for the emergency room instead.

Medicaid covers millions of rural Americans who don’t have easy access to doctors, and particularly specialists. And even if they did, Medicaid’s low reimbursement rates have led many doctors to refuse taking new Medicaid patients.

In addition, the Medicaid population has a higher incidence of chronic medical conditions than the general population, and a disproportionate share of smoking and obese populations, putting them at greater risk of high-cost medical episodes.

The Mobile Device as a Medical Home

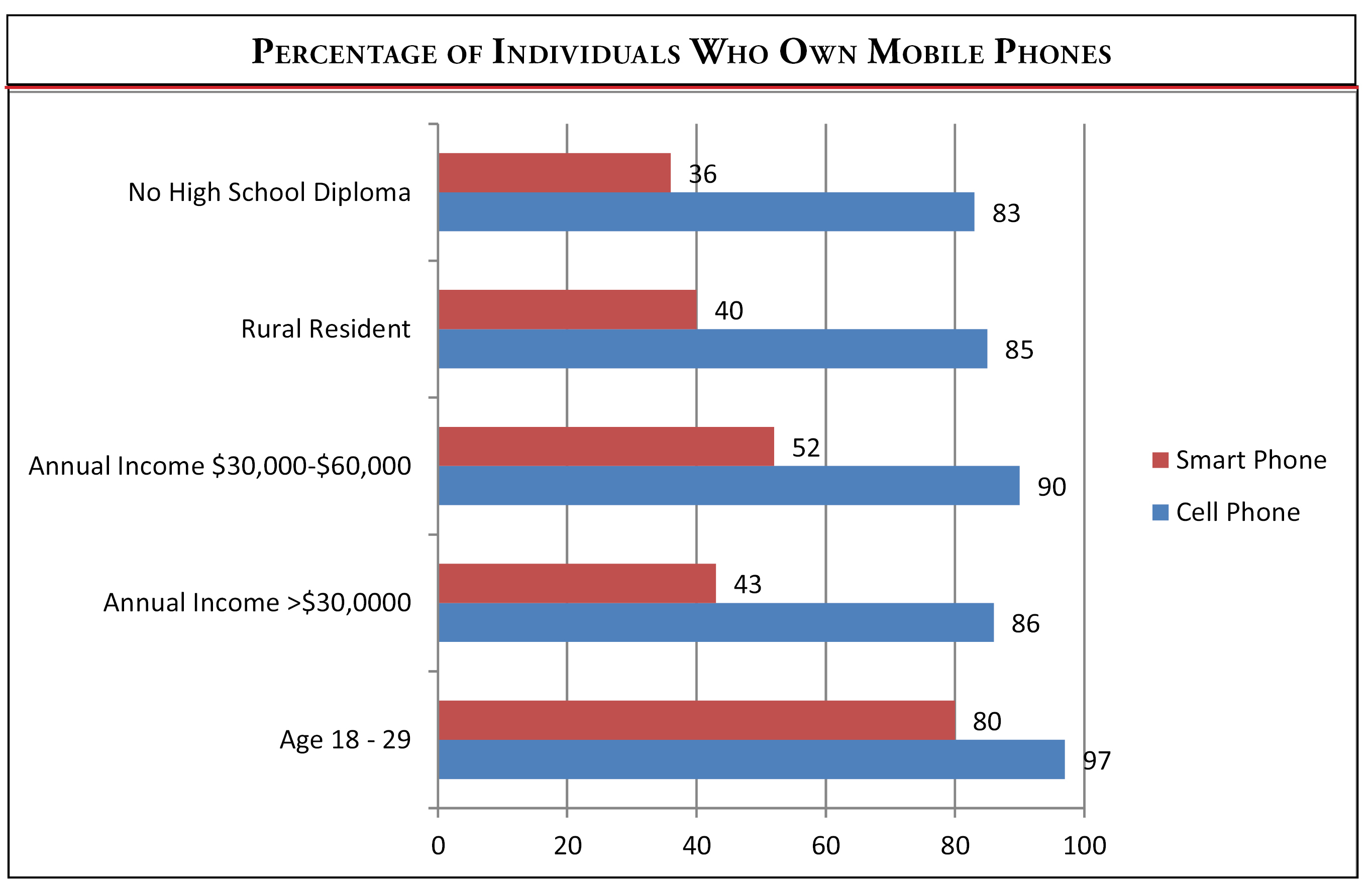

However, low-income populations have a high penetration of mobile phones. The Pew Research Center says that [see graph]:

- 86 percent of households making less than $30,000 a year have a mobile phone (but only 43 percent have a smart phone), and 90 percent for those making between $30,000 and $50,000;

-

85 percent of rural households have a mobile phone;

-

And since the poor tend to be disproportionately younger households, it’s important to note that 97 percent of those between the age of 18 and 29 have a mobile phone.

That means if we really want the Medicaid population accessing health care, their mobile device could become their "medical home." How can we do that?

How Technology Could Help Medicaid

There are a number of ways that existing technology widely available to consumers—referred to as "edge of the network" technology—is already being applied to health care. This field is broadly referred to as health IT, and it can include mobile devices, including mobile phones as well as notebooks, but also the use of applications and video connections, called telehealth.

Integrating health IT into Medicaid could actually address many of the challenges faced by the Medicaid population.

Continuation of Care—Low-income patients don’t naturally gravitate to a "medical home," so we need to create a mobile medical home that takes advantage of mHealth visits. Wireless medical devices could monitor some chronic conditions and let the health care provider know if a problem arises.

Doctors’ appointments—Given the job constraints and travel challenges facing many low-income and unemployed workers, especially mothers with young children, a virtual doctor’s appointment could be the first option, with an in-person visit occurring only when necessary.

Pharmacy—Pharmacists are actively looking for more ways to be involved in patient health, and they are developing apps to help patients manage their pharmaceutical needs and usage. But they could be much more involved by monitoring when and what drugs Medicaid patients use.

Compliance—Compliance with drug and medical regimens is a challenge for any demographic group, but especially with low-income populations. Regular texts could be sent to Medicaid beneficiaries’ mobile phones reminding them that it is time to take their medication.

Chronic care management—According to the Centers for Disease Control, about 75 percent of health care spending is on chronic diseases. Helping Medicaid patients monitor and manage chronic care diseases could dramatically lower health care costs and improve their quality of life.

Lifestyle changes (smoking/obesity/sedentary)—Low-income populations have a higher incidence of smoking and obesity. And many don’t exercise regularly. There are mHealth services that encourage people to change that behavior. Participation in such programs should be mandatory for those on Medicaid.

Home monitoring/long term care—The disabled and long term care populations are responsible for the lion’s share of Medicaid spending. Helping them remain in their homes while monitoring their care could lower the need for nursing home care and in-home visits, and reduce the need for them to make difficult visits to their health care provider.

Telehealth/remote access—The poor often live in small and rural communities where there is little or no access to physicians, and particularly specialists. Both distance and the inability to take off from work without economic consequences affect rural populations. The Veterans Administration has demonstrated the value of telehealth services extensively, covering 80,000 people in 2012 with 200,000 visits.

While nurse practitioners have increasingly been stepping into this role, the poor still need access to a doctor. Virtual appointments with distant physicians, perhaps coordinated by the local nurse, could facilitate their access to care.

Personal health records—Medicaid could set a standard by creating a personal health record for each beneficiary, which allows individuals to keep some basic health information readily available. Health care providers would need easy access to it, and they need to be able to record any care delivered or monitor it for unusual or inappropriate care, such as too many prescription drugs (such as painkillers).

While the general population has yet to widely embrace PHRs, by using the 50 state Medicaid programs as laboratories of innovation, we may discover a system that is both functional and useful.

Conclusion

Technology is opening new doors to health care reform, and Medicaid could play a leading role in that effort. But neither the states nor Washington have embraced health IT for Medicaid. The goal of health care reform was to increase access to care, lower costs and improve quality. It is doubtful that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will achieve any of those goals, but integrating technology into Medicaid coverage could.