Due to the breakdown of the multilateral trade liberalization process at the World Trade Organization (WTO), the United States has continued to pursue trade liberalization with individual nations or groups of nations through bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs). A number of FTAs have been successfully negotiated over the past two decades, and today the U.S. has free trade agreements with 20 partner countries.

These FTAs have succeeded in lowering trade barriers between countries, thus increasing overall trade and imparting demonstrable value to both the U.S. and its FTA partners.

IP in FTAs

At the behest of the U.S, these agreements have generally included sections on the protection of intellectual property (IP). While initially noncontroversial, objections have increased with each succeeding FTA over U.S. insistence that FTA partners raise their IP protection standards to more closely approach those of current U.S. law.

This tension over including IP in trade agreements came to a head over the proposed Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), which focused on IP issues. Negotiated over a six-year period, 31 countries signed the agreement, but protests by activists and NGOs critical of IP protections cowed the European Parliament into rejecting ACTA in 2012, even though 22 European countries signed the agreement.

The collapse of ACTA has emboldened IP-skeptic activists and NGOs toward even greater opposition to including IP protections in subsequent proposed FTAs such as the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), which is being negotiated between a dozen countries, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP), which is being negotiated between the U.S. and the E.U. These agreements, intended by their negotiators to become new international standards, are facing heightened criticism over their IP chapters, although more traditional trade flash points such as agricultural and automobile protections are still the largest obstacles to an agreement.

While it is not surprising to find NGOs created for the sole purpose of opposing intellectual property protection fighting to keep it out of trade agreements, those efforts could persuade some who favor trade liberalization to jettison IP protections in current and future trade agreements.

IP Goods Dominate U.S. Exports

Some have argued that the U.S. only insists on including IP protection "at the behest of a narrow set of industries " or special interests.

For example, listening to the rhetoric of IP skeptics in the blogosphere and social media, one would think that the IP industries are an insignificant part of our economy, and that the only reason IP is included in trade agreements is due to the IP industries’ lobbying efforts and their influence with the federal government and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR).

But an examination of the data demonstrates that IP goods are far from a narrow set of industries or a small portion of U.S. exports. Indeed, the IP industries are the largest category of U.S. exports.

Figure 1, using U.S. Census Bureau data, extracts the pharmaceutical and biotech exports from chemicals, where they are usually categorized, and stacks them on top of the copyright exports. The result is the "core" IP industries—copyright and pharmaceuticals. As the figure shows, the core IP industries make up the largest category of U.S. exports.

This fact—that the core IP industries are the largest category of U.S. exports—is probably a surprise to many. But Figure 1 should raise additional questions. After all, aren’t significant portions of the chemical, aerospace and other industries also dependent on IP protection? Indeed they are—many of the products of our aerospace design and manufacturing industry are protected by patents, as are chemicals, enzymes, and even patented seeds and crops. So an analysis based solely on copyright and pharmaceuticals, as impressive as it is, doesn’t accurately measure the total importance of IP goods to U.S. exports.

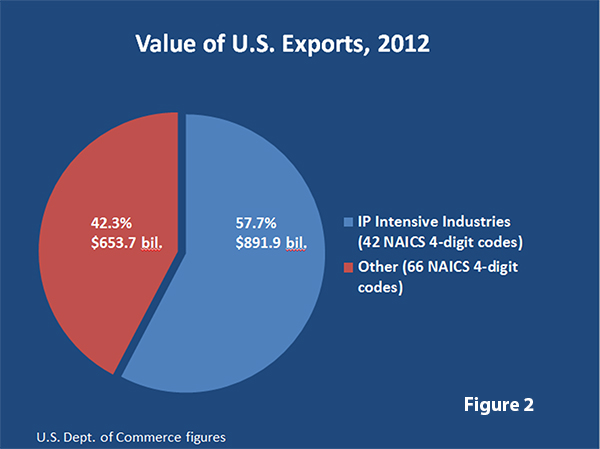

That’s why the Department of Commerce has identified what it calls the "IP intensive" industries. Using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), the Commerce Department determined that 42 of the high level (4 digit) NAICS codes comprise the IP intensive industries, leaving 66 non-IP intensive industry categories. Figure 2 shows that, when U.S. exports are allocated according to these two divisions, 57.7 percent of U.S. exports in 2012 (and usually right around 60 percent in the last several years) are from the IP intensive industries.

This dominance of IP goods over other categories of U.S. exports is almost certainly surprising in light of public rhetoric and activism, but it underscores the fact that the world buys from the United States the products of our innovation and creativity—and those products tend to be protected by some form of intellectual property. Creativity and innovation is the U.S. competitive advantage in trade.

Much of the U.S. Economy Depends on IP

Trade, of course, is fundamental rather than ancillary to an economy. Exports drive job and wealth creation in the domestic economy, and so it’s logical to assume that, if the U.S. stops demanding strong IP protection from its trading partners, that would threaten at least a portion of the domestic IP economy.

So it’s worth noting the contribution of the IP industries not only to U.S. exports but also to the U.S. domestic economy, which is significant. According to a 2012 Department of Commerce study using 2010 data, the IP intensive industries:1

-

Directly account for 27.1 million jobs, or 18.8 percent of all employment;

-

Indirectly support 12.9 million additional jobs, totaling 40 million jobs or 27.7 percent of total employment;

-

Account for $5.06 trillion in value added, or 34.8 percent of U.S. GDP; and

-

Account for 60.7 percent of total U.S. merchandise exports.

In light of these facts, to exclude IP protections in free trade agreements would be malpractice for U.S. trade negotiators. It is clearly in U.S. interests to include IP protection in trade agreements, and it is in fact other issues such as labor and environmental protections, routinely included in trade agreements, that are less critical to U.S. trade.

Higher IP Standards Benefit Our Trading Partners

What about the argument that the U.S. should not impose higher standards of IP protection on our trading partners? A trade agreement that would enrich the U.S. at the expense of its trading partners sounds more like mercantilism than free trade.

But, in fact, numerous studies have found a correlation between higher levels of IP protection and stronger economic growth.

-

According to a 2008 OECD study, stronger patent rights in developing countries are a significant determinant of levels of foreign direct investment (FDI), and also facilitate higher levels of technology transfer.2

-

A 2012 OECD study found that a 1 percent change in the strength of a country’s IP framework is associated with a 2.8 percent increase in foreign direct investment inflows and a 0.7 percent increase in domestic R&D.3

-

And a 2013 study found that R&D spending has grown relative to GDP in developing countries after they adopted the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).4 The study also found that medicines for developing countries had received additional funding, and that the TRIPS agreement had directly contributed to the emergence of native film industries in African countries.

So not only is protecting IP in trade agreements in the interests of the U.S. economy, it’s also in the interests of our trading partners. It’s a win-win.

It’s About IP, Not Trade

But if higher IP protection standards are good for all parties to an FTA, why is there so much controversy? Ultimately, it’s IP protection itself that is the issue, not its inclusion in trade agreements. The same activists, NGOs and bloggers who oppose IP protections in trade agreements also favor weakening or eliminating IP protection altogether. And many of them support the inclusion of labor protections and environmental standards in trade agreements, so they clearly aren’t trade "purists"—i.e., they don’t mind using trade agreements as leverage to promote policies that they favor. They just don’t like IP rights.

Ultimately, those who argue against IP protection in trade agreements are simply carrying their general skepticism about IP into the trade policy arena, so the controversy should be recognized for what it is: a philosophical dispute over IP that has spilled over into trade policy. Setting that philosophical dispute aside and focusing on the data demonstrates that, for the U.S., protecting IP in trade agreements should be a no-brainer that benefits our trading partners as well.

Conclusion

Despite rhetoric from NGOs, activists and others engaged in a campaign to erode support for intellectual property rights, a fact-based analysis reveals that IP goods are the largest share of U.S. exports and support a significant portion of the U.S. economy. The U.S. economy is increasingly dependent on the products of innovation, creativity and invention, and so policies that support innovation and creativity should be priorities for the U.S. government, especially in trade agreements. And nudging our trading partners toward greater respect for intellectual property rights also turns out to be in their best interests.

Endnotes

1. Department of Commerce, “Intellectual Property and the U.S. Economy: Industries in Focus” (April 2012, based on 2010 data)

2. O.E.C.D Trade Policy Working Paper No. 62, “Technology Transfer and the Economic Implications of the Strengthening of Intellectual Property Rights in Developing Countries,” Walter Park & Douglas Lippoldt, 2008

3. O.E.C.D. Trade Policy Working Paper No. 104, “Policy Complements to the Strengthening of IPRs in Developing Countries,” Gaurav Tiwari, 2012.

4. “TRIPS at 20: Patenting, Public Health, and an Agreement That’s Working,” Edward Gresser, ProgressiveEconomy, 2013.