Synopsis

The Obama Foundation is now building the massive Obama Presidential Center in Chicago’s Jackson Park, designed by the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. But that venture is fraught with massive difficulties, as its poor location misses valuable opportunities to improve overall land use and economic development in Chicago from putting it elsewhere. The Foundation’s sweetheart deal with Chicago violates the public trust doctrine, and the actual transfer took place without the Foundation meeting either its financial preconditions or the multiple environmental laws protecting key public landmarks. Even at this late date, the deal should be undone.

Introduction

The decision of Barack and Michelle Obama to build the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) in Jackson Park has generated much controversy since it was first announced in 2015. The opposition has never been toward the construction of the OPC on Chicago’s South Side, which “is the community where Mrs. Obama was raised, where President Obama got his start in organizing and politics, and where they started their family.” The announcement sparked general approval about the prospects of the Center and generated among his ardent supporters a combination of “general excitement and extreme concern.” The excitement was the anticipation of a world-class facility on the South Side of Chicago, which could be both a cultural landmark and an engine of economic development in the relatively underinvested region. The anxiety was that the benefits could be largely appropriated by the Foundation itself or the powerful elements in society.

Building the Obama Presidential Center in Jackson Park

Given this background, there was general approval of having the Center built on the South Side of Chicago. To the public, the key point of contention, however, was the decision of the Obama Foundation, strongly backed by the city of Chicago and most of Chicago’s grandees, to build the Center in Jackson Park, within a stone’s throw of Lake Michigan. That public uneasiness was not because of any impact that the Center might have on the visual and aesthetic integrity of Jackson Park, a nineteenth-century masterpiece of Frederick Law Olmsted, the foremost landscape architect of that (or perhaps any) historical period.

No, the key opposition to the program was first to the strong refusal of the Obama Foundation to sign a community benefits agreement (CBA) with leading groups of Chicago’s South Side: as early as 2018, the multi-millionaire former president was reported by Chicago’s Reader as insisting publicly, “No community benefits agreement, and let’s move on.” He then explained: “If we sign with one, two, or five organizations, they’re not representing everybody on the south side. Next thing you know, you’ve got 40 or 50 organizations—all wanting to be decision makers. We’re not going to do that.” That point is true of all CBAs, and it did not quiet the uneasiness. From that date forward, the activists within the community have raised fears of gentrification and have presented the Obama Foundation with the demands that it make no investments that would “displace the community’s Black residents.” The list would include spurring the development of more affordable housing with money from Chicago’s Low-Income Trust Fund, coupled with a tax forgiveness program for low-income residents. Many of these disputes would crop up no matter where the OPC was located on the South Side. But by the same token, the current debate over gentrification is made far more acute by putting the Foundation in a highly packed area, where most of the nearby land is already developed, thus tying gentrification and displacement closely together.

The anxieties have only increased with the passage of time. Today, local residents all fear displacement. The owners think that an increase in property values would drive up already-high real estate taxes, which in turn would force them to sell and move out of the neighborhood. The renters fear that, at the expiration of their leases, the landlords would jack up their rents and thus force them out of the neighborhood. As is true in all these gentrification debates, the locals tend to ignore the interests of those outside their immediate community. No South Side voter considers the disappointment that outsiders experience when blocked from moving into the neighborhood. Nor is any local voter concerned with the lost tax revenue when land values are kept artificially low. And local voters do not much care about the increased economic activity that would arise if new owners and landlords were to invest in their now dormant properties.

One way to have avoided these acute conflicts was to move the OPC out of Jackson Park to some alternative location on the South Side—most notably just to the west of Washington Park—where the preferred site, itself largely vacant, would be adjacent to extensive areas of vacant land. So relocated, it would now be easy for private developers, backed by a cooperative mayor and city council, to build new housing projects, both market-rate and affordable, without displacing current tenants, and, indeed, by improving the safety of their neighborhoods in the process. Yet strangely, anyone could look high and low for a reasoned statement from the Foundation why it rejected all these alternative sites. The conscious reticence on this issue stands in sharp contrast to Obama’s defense of “transparency and open government,” which he made the day after he became president: “My Administration is committed to creating an unprecedented level of openness in Government. We will work together to ensure the public trust and establish a system of transparency, public participation, and collaboration.” And he repeated that pledge in June 2016, insisting that in Freedom of Information requests “agencies should adopt a presumption of openness.” But in private life it is better to stonewall the public as he has done. Thus, the official site of the Foundation celebrates the choice of site as a given, and then extols its supposed advantages for the community at large: “creating jobs, driving economic opportunity, and unlocking the potential that has always existed on the South Side. By tapping into the boundless talent of neighborhoods throughout Chicago, it will become a campus for the community, built in partnership with the community.”

Plantiffs’ Legal Challenge to the OPC

It should come as no surprise that placing the Obama Presidential Center in Jackson Park has spurred legal action against the Foundation, which would not have ever been contemplated if the Obamas had not chosen prime publicly-owned real estate for their private Foundation. Indeed, all legal issues would have disappeared, and the Foundation would now be up and running if it had chosen a more accessible and less-expensive site for its venture. The plaintiffs in these lawsuits have been led largely by Protect Our Parks (POP), and joined by several Chicago residents, who today are represented by myself and Chicago lawyer Michael Rachlis, who has long specialized in these land use issues. These lawsuits began in 2018 before Rachlis and I got involved in the case a year later. During that initial period, some preliminary decisions had been already made on the case by Judge John Robert Blakey, a Notre Dame graduate who had been appointed to the Northern District by President Obama in 2014. The litigation continues to be active to this very day, as right now the case is on Appeal to the Seventh Circuit. Thus far we have been unsuccessful in our sole objective: to stop the construction of the OPC in Jackson Park, while fully supporting its construction at a superior South Side site located just west of Washington Park. In this article, my main purpose is to fill a gap in the public discourse by explaining why and how the legal arguments against the OPC are far stronger than appears from the decided cases.

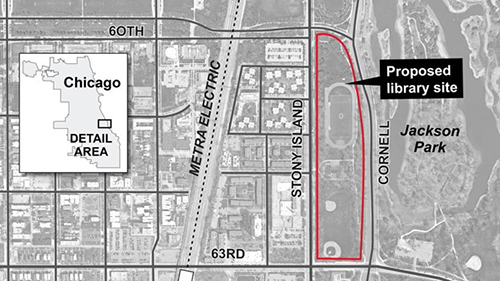

At root, this ongoing dispute of over four years involves a conflict of two visions for the OPC. The Obamas, backed by a formidable array of public officials and local dignitaries, have set their sights on building the OPC in historic Jackson Park—a masterpiece of landscape architecture designed by that greatest of landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903). Their plan calls for taking 19.3 prime acres in the heart of the 551-acre park of which roughly 350 acres are water. The project goes beyond those 19.3 acres by taking over roughly 10 additional acres of parkland to expand the roadwork on both Stony Island Avenue to the west and Lake Shore Drive to the east, and converting Cornell Drive (which runs north-south between the two) into a bike path. These acreage figures may seem small, but they are in fact huge: the land taken is by far the most valuable in the park given the centrality of its location and the current intensity of its use.

If allowed to be completed, the OPC project would uproot close to 1,000 mature trees and disrupt major migratory bird paths that run north-to-south along the shore of Lake Michigan. In total, the public cost of the new roadwork—borne by both the federal government and Illinois, but not the Obama Foundation, of course—probably exceeds $300 million dollars (and growing with inflation), ultimately leaving the already overtaxed and congested system with three fewer north-south lanes than before.

The OPC would command an impressive view of the Lake Front, and up and down the Midway Plaisance. But the location would be difficult for visitors, employees, and suppliers to reach. It is located on a cul-de-sac, which means that all vehicular activity is concentrated at a single point that would permanently slow down all three groups getting into the building. The OPC is also located over a high water-table, adjacent to the West Lagoon just off and connected to Lake Michigan. Its main 235-foot tower would have to be protected by some dewatering scheme that could well require pumping on a 24/7 basis to keep water out, even before any major storms or other severe weather events damage the center. The OPC is expensive to secure because the tower will contain living quarters for President and First Lady Obama, which need protection not only when the couple are in residence, but year-round. Given its isolated Hyde Park location, it cannot serve as the sparkplug for any new businesses. Note that it sits just to the south of the far larger Griffin Museum of Science and Industry, which for decades has generated virtually no new business for Hyde Park.

The construction of the OPC is for the Obamas only the first stage in their effort to take over Jackson Park; lurking in the wings is their plan for the construction of a professional-level golf course, which would at a minimum turn the Shore Nature Sanctuary into the 14th and 15th holes for the new professional golf course, and would require—the number is contested—cutting perhaps 2,000 old-growth trees—to make way for the course. In a nonbinding referendum held in November 2022, local residents “overwhelmingly voted to oppose the removal of thousands of trees because of construction around the Obama Presidential Center and a proposed golf course project.” There is of course no good reason to locate that massive golf course in the park when so many alternative sites are less disruptive and more conveniently located to public transportation. So in what may turn into a reprise of the fights over the OPC, the grass-roots community resistance mobilized by, among others, Save Jackson Park, hope to stop this project before any litigation is needed.

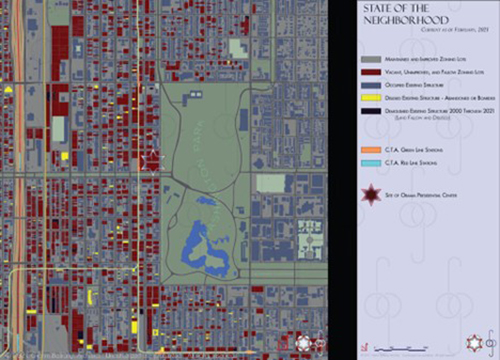

The same unfortunately cannot be said about the OPC, now subject to intensive litigation. Yet, in an effort to forestall litigation, the noted landscape architect, Grahm Balkany, prepared an alternative plan which would sit on an estimated 10-acre plot located just to the west of Washington Park. Here is his site map, which is coupled with this comprehensive tour of his plan Twin Embraces:

An Inclusive Vision for the Barack Obama Presidential Center

Twin Embraces (c) 2020-2021, Grahm Balkany: Architect. All Rights reserved. www.OPCWashPark.US

Above: To-Scale study of current Land Use in the Washington Park Neighborhood

Population Trends Study Results Enlarge Legend

This alternative vision is a far better deal for both the OPC and the surrounding community. It borders two major roads—Garfield Boulevard going east-west, and Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, going north-south—and is located over the Chicago Transit Authority’s Green Line and near the Red line. The location’s proximity to the Dan Ryan Expressway is an added benefit. Access is easy, the cost of construction is surely far lower, and the disruption of city and through-traffic will be minor at worst. The site is not located near any large bodies of water, and it will sit on private land that requires no government permitting. It would almost certainly be received warmly by the surrounding community, since the site sits near a poor, underserved, largely African American population, an area with much vacant land whose redevelopment could be spurred by locating the OPC nearby. Finally, this alternative site does not require the destruction of a world-class park. On a straight up comparison, the proposed OPC dominates the chosen Jackson Park site in every relevant dimension. Nonetheless, at no point in the litigation has either the city or the Foundation had to explain why they turned down this plainly superior site, despite legal challenges by POP to the construction of the OPC in Jackson Park.

That litigation is broken into three distinct components. The first involves the environmental issues associated with the placement of the OPC in Jackson Park. The second deals with the public trust doctrine. The third covers the prosaic business issue of whether the OPC has met the financial and business terms of its contract with the city that would allow it to take possession of the OPC site.

1. The Environmental Issues

The environmental challenges to the OPC turn on the requirements of two key, overlapping statutes: the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) and the Transportation Act of 1966 (TA). NEPA is a disclosure statute intended to ensure that all key actors, both public and private, take into account all relevant considerations before any such transportation project may be undertaken. But these disclosures are often exacting, a fact which has led to extensive delays in the construction and renovation of major projects such as airports, train stations, power plants, and highways. Consequently, NEPA has been subject to extensive criticism, including my own writings, because of how its onerous disclosure requirements routinely delay—often for years—construction of new roads and airports needed to keep the transportation grid alive. In contrast, the construction of the OPC has led to “major traffic headaches” in Chicago’s Hyde Park and across the South Side. For its part, the Transportation Act tracks the requirements of NEPA, but further requires the consent of the secretary of transportation or his subordinate under Section 303(c) (commonly called Section 4(f)) before construction may commence.

The gist of the challenge therefore lies in the basic purpose of these two statutes, and the conscious efforts on the part of their drafters to ensure that any public or private party that starts a major project covered by these statutes cannot evade its requirements. It is undisputed that NEPA applies “only to major Federal actions,” 42 U.S.C. § 4332(C), which by regulation also covers those actions “which are potentially subject to Federal control and responsibility,” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.18 (2019). The projects that are so subject include those which receive any federal funding in whole or in part. It also has long been accepted that an entire project counts as a major federal action, even if federal money has only been spent on its initial stages. Scottsdale Mall v. State of Indiana, 549 F.2d 484 (7th Cir. 1977).

At this point, the key question is whether the OPC falls under these statutory requirements. In its Assessment of Effects report of January 2020, the federal government noted:

the undertaking comprises the construction of the OPC in Jackson Park by the Obama Foundation, the closure of roads to accommodate the OPC and to reconnect fragmented parkland, the relocation of an existing track and field on the OPC site to adjacent parkland in Jackson Park, and the construction of a variety of roadway, bicycle and pedestrian improvements in and adjacent to the park. The Federal actions proposed include the funding of roadway improvements and bicycle and pedestrian enhancements by FHWA [Federal Highway Administration].

Section 4(f) of the Transportation Act then further explains that under the applicable federal policy, “a special effort” must be made to protect public parks, such that a transportation project can be approved only if:

(1) there is no prudent and feasible alternative to using that land; and

(2) the program or project includes all possible planning to minimize harm to the park, recreation area, wildlife and waterfowl refuge, or historic site resulting from the use.

Any sensible reading of these provisions would suggest that the Washington Park site must be considered one of those “prudent and feasible alternatives.” But the January Assessment of Effects Report took the position that no such review was needed, because (1) all the changes were “local,” and (2) “These actions are not transportation projects” because they “are being implemented to address a purpose that is unrelated to the movement of people, goods, and services from one place to another.”

No explanation is offered for why expanding two major roadways and shutting down a third to both intrastate and interstate vehicular traffic, converting it to a bike path, does not count as a transportation project. Instead, the entire matter was finessed by several sleights of hand. The Seventh Circuit treated this as a local project because the federal government could not “dictate” the location of the project. But that is true of every local project, each of which is subject to federal review because each must meet the full requirements of NEPA. Thus, the secretary of transportation or his delegate can refuse consent under the TA, leaving the local government free to start proceedings anew at a different location.

All of the 2919 hearings in 2019-2020 were undertaken on the assumption that the OPC and the road were part of a signal project. Long afterwards, however, the defendants sought to wiggle out from oversight by giving a new definition to their Jackson Park project on February 8, 2021, that inexplicably made no mention of the OPC in its “final agency actions,” and offered no explanation for its change from the earlier definition.

The proposed construction along Lake Shore Drive, Stony Island Avenue, Hayes Drive, and other roadways in Jackson Park and the construction of proposed trails and underpasses in Jackson Park, Cook County, Illinois.

This truncation of the project definition is in flat contradiction to the central tenets of these environmental review processes. Back in 1971, the United States Supreme Court was faced with the question of whether to allow local officials to build a new expressway through the heart of Overton Park, located in Memphis, Tennessee. When the question arose as to the duties of secretary of transportation under Section 4(f) of the TA, as overseen by the federal courts, Justice Thurgood Marshall gave this canonical answer in Citizens of Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402 (1971):

Even though there is no de novo review in this case . . . the generally applicable standards of § 706 [of the Administrative Procedure Act] require the reviewing court to engage in a substantial inquiry. Certainly, the Secretary’s decision is entitled to a presumption of regularity. But that presumption is not to shield his action from a thorough, probing, in-depth review.

This passage, which has been relied on in literally thousands of cases, is somehow never quoted in full by the Seventh Circuit, the District Court, or the defendants. The drafters of NEPA were well aware that regulated parties would be prepared to manipulate that “project” scope to evade all environmental review. For this reason, the regulation covers “all projects and programs entirely or partly financed, assisted, conducted, regulated, or approved by federal agencies.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.18(a). Thus, in Citizens against Burlington, Inc. v. Busey, (D.C. Cir. 1991), then-Circuit Judge Clarence Thomas cautioned: “Yet an agency may not define the objectives of its action in terms so unreasonably narrow that only one alternative from among the environmentally benign ones in the agency’s power would accomplish the goals of the agency’s action, and the EIS would become a foreordained formality.” Ironically, right after citing Busey in its initial response of August 19, 2021 to plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction, the Seventh Circuit does the exact opposite: “The City’s objective was to build the Center in Jackson Park, so from the Park Service’s perspective, building elsewhere was not an alternative, feasible or otherwise.” [A.058, 8/19/21 Seventh Cir. Opinion at 8]. Note Washington Park comes into play even if the Foundation wanted to build, as it still proudly proclaims, the OPC on the South Side of Chicago, which includes the Washington Park area.

Dodges like this are verboten, so any effective NEPA or TA review must stop the insidious practice of “segmentation,” whereby a single project is broken into two or more smaller ones, thereby bypassing the necessary administrative review. In this instance, the government segmented the original OPC project into two parts: first, the construction of the OPC, and second, the widening of other roadwork in Jackson Park. Under NEPA and the TA the necessary, probing review goes as much to project scope as it does to anything else.

Note the huge stakes of this characterization dispute. The Seventh Circuit wholly ignored the segmentation question with the simplistic observation that “NEPA reaches only major a federal actions, not actions of non-federal actors.” The last half of this sentence is flatly incorrect. All sorts of actions by non-federal actors are caught by NEPA if they receive any federal funding, as is the case here. This misconstruction gives any state-initiated project a free pass. Thus, once the segmentation takes place, it is no longer necessary to conduct a thorough and straight-up comparison between the Washington Park site and the Jackson Park site, because once the construction of the OPC is treated as a given, the only federal project is the subsequent adjustment of the roads abutting Jackson Park. Obviously, something has to be done, so the federal government, the city, and the Foundation got their way by doing an exhaustive examination of the wrong question—how best to close down Cornell Drive and expand both Stony Island Avenue and Lake Shore Drive.

Without illicit segmentation, the project is doomed. The plaintiffs sought a preliminary injunction to stop construction and the cutting of trees until that legal issue was resolved. The applicable standard was the four-part test articulated Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008):

A Plaintiff seeking a preliminary injunction must establish that he is likely to succeed on the merits, that he is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, that the balance of equities tips in his favor, and that an injunction is in the public interest.

This test has four parts, of which the Seventh Circuit addressed only the first—the likelihood of success on the merits— and it even did that evaluation inadequately. By looking at the whole project, it was evident that this administrative review was fatally defective because the federal officials never addressed the Washington Park alternative. And if the government were to do so, the defendants’ case on the last three factors would quickly crumble. In every case but this one, the destruction of trees and the disruption of migratory bird patterns both require powerful justifications. One of the most common is that the repair or location of an essential facility has to be done at a given location if it is to be done at all. For example, a tunnel or bridge cannot be moved; nor could the additions to a baseball field which connect the field to the park. And even then, the destruction of a thousand trees might well doom the expansion plan. But the OPC is a freestanding facility, which could be located anywhere on the South Side, including on land adjacent to Washington Park, which has few trees and lies far away from the migratory bird routes. The harm from construction in Jackson Park is both irreparable and avoidable.

Jackson Park’s situation is in sharp contrast with the established precedents, where any finding of proper segmentation is always preceded by a close factual examination of whether the two projects are indeed separable. Thus, in Highway J Citizens Grp. v. Mineta, (7th Cir. 2003), the court allowed for the highway repair only after it was proved that project did not emit a “contamination plume” that reached the Ackerville Bridge/Lovers Lane project, eliminating the need for either coordinated work or coordinated financing. In Neighborhood Ass’n Inc. v. Kauffman, (7th Cir. 2003) there was both physical and financial separation between the local project in Goshen, Indiana, from roadwork on U.S. Highway 33 outside the city. In Sierra Club v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs, (D.C. Cir. 2015), the Court held an NEPA review of an entire 593-mile pipeline was not needed because the physical repairs at each location were “wholly independent” of work at all other locations. But segmentation was rejected when repair work at one location necessarily impacted operations at other points on the pipeline. Delaware Riverkeeper Network v. FERC, (D.C. Cir. 2014). There is no physical separation, no temporal separation, and no financial separation in Jackson Park between the OPC and its network of road changes. Federal moneys could not be separated between funds used to benefit the OPC and influence the road grid. The failure to offer any evidence on the key issues of separability makes the decision of the Seventh Circuit clearly erroneous.

Sadly, against this uniform backdrop, the Seventh Circuit never asked the City or the Obama Foundation to examine any of the voluminous evidence the plaintiffs presented both in their opening and reply briefs on this key environmental comparison. The Court accepted the “exhaustive Technical Memorandum that . . . confirms that each tree lost will be replaced by newly planted trees,” without once mentioning that the new trees would be two- or four-inch diameter saplings planted only after the OPC construction is completed, all of which will take years to reach maturity. It further did nothing to justify the statement that “dying trees will be replaced by healthy ones” and failed to acknowledge that the defendants’ own study revealed that some 92 percent of the existing trees “were in good or fair conduct.” It then claimed that there are lots of healthy trees left in other parts of Jackson Park, without once acknowledging that the ratio of trees killed to trees preserved has never been accepted as an adequate review in any NEPA proceeding. It also took the astonishing position that in the long run, the deracination of Jackson would be “overall neutral,” when in present value terms, the substitute plan will supply far less than 1 percent of the total benefit of the current configuration, even ignoring the high costs of transition and the massive short-term disruption and aesthetic blight in Jackson Park. The Court’s conclusion that “NEPA requires no more” is therefore an utter whitewash of a deplorable situation. That brief judicial discussion took place without a single citation to any case, regulation, government publication, or scientific finding, notwithstanding the mass of contrary evidence plaintiffs presented to the Court. That back-of-the-hand treatment hardly qualifies as the “thorough, probing, in-depth review” demanded of the Seventh Circuit.

The balance of equities is equally easy—for it is only the Obamas who sought the more exclusive lakefront location, and who were able to persuade the city to move the project further north (where it closes part the northbound lanes of Cornell Drive and towers over the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry), solely in order for the structure to be seen across the Midday. Nor is the OPC entitled to bonus points because it rushed (see below) the groundbreaking after it received multiple warnings that this project offended the NEPA and the TA. No amount of study could make the project look respectable under NEPA or justify the required approval from the secretary of transportation, which was given here. The OPC fails by a mile to meet the NEPA and TA standards.

2. The Public Trust Side

Prior the completion of the NEPA study, the plaintiffs had brought a claim for the breach of the public trust doctrine on two separate occasions, first in 2019 and then in 2021. The basic duties of a trustee of both private and public property have been set out (2010) by Robert Natalson as follows:

A. The Duty to Follow Instructions and Remain Within Authority;

B. The Duties of Loyalty and Good Faith;

C. The Duty of Care;

D. The Duty to Exercise Personal Discretion;

E. The Duty to Account; and

F. The Duty of Impartiality.

Elsewhere, Natalson has written (2004) emphatically: “I have not been able to find a single public pronouncement in the constitutional debate contending or implying that the comparison of government officials and private fiduciaries was inapt.”

All of these duties are in play in this case. In the first action, filed in 2018, the plaintiffs claimed that the entire deal was a violation of the classic fiduciary duties, insofar as the city and the Obama Foundation entered into a sham transaction that transferred public lands under a 99-year “use agreement” worth perhaps as much as $200 million for $10 in cash, coupled with a promise (not yet honored) to take financial responsibility for the construction of the OPC out of its own resources.

But note the twists and turns. In a 2016 decision involving the construction of the Lucas Center elsewhere along the Chicago Lakefront, the late District Judge John W. Darrah ruled in Friends of the Park v. Chicago Park District (FOTP) that the city and the Lucas Center had to go through a full examination under the public trust doctrine because they had taken a 99-year ground lease (with options to renew for two additional 99-year terms), which was tantamount economically to a conveyance of outright title of the parcel to the Lucas Foundation. Duly warned, the Foundation and the city morphed the original 99-year lease into a 99-year “use” agreement, in which “title” to the property remained with the city—a position that the district court fully embraced for the OPC. But at no point could anyone point to any economic difference between this use agreement and an ordinary lease. So, in a rerun of the segmentation doctrine, a small terminological difference—ground lease versus use agreement—was allowed to circumvent the prohibition against giving away public property to private entities for a song.

The evident imbalance in the receipt of $10 for perhaps $200 million in land use to the OPC flunks the basic good faith standard for all fiduciaries public or private. Indeed, the situation is even worse than usual because the deal was in no sense at arm’s length, given the obvious conflicts of interest from day one. Chicago’s mayor in 2015 was Rahm Emanuel, who had previously served as Obama’s chief of staff in the White House until he resigned in October 2010 to run for mayor of Chicago. And once in office, the all-democratic city council delegated the decision on where to build the OPC to the Obama Foundation, stating in 2015 (before the Library became a Center in 2018) that “the City defers to the sound judgment of the President and his Foundation as to the ultimate location of the Presidential Library.” Nor can these truncated procedures or this lopsided deal be salvaged by claiming “indirect” benefits to the city and its residents from the construction of the OPC in Jackson Park, because, as noted above, all the communal benefits from building an OPC near Washington Park (ease of transportation, environmental amelioration, neighborhood stimulation) dwarf those from building the OPC in Jackson Park.

At this point, the litigation turned on the technical requirement of “standing” needed to bring any action in federal court. Standing generally requires that an individual plaintiff show a discrete and concrete interest that is separate and apart from that of all other citizens. This requirement is not commonly imposed by state courts. Thus, in the key 1970 case of Paepcke v. Public Building Commission of Chicago, several citizens of Chicago who lived next to Washington Park sought to stop the construction of a public school on just under four acres of adjacent public parkland. The project involved the intergovernmental transfer of land from the Park Department to the Public Building Commission, with no private beneficiaries. It was agreed that the construction of an ordinary school was no kind of nuisance, either public or private. Thus, Paepcke held emphatically, in line with well-established Supreme Court precedent, that the plaintiffs could not circumvent the nuisance requirement by claiming that they had some “implied easement” that allowed them as neighbors to block the schoolhouse.

Yet the plaintiffs had a second arrow in their quiver, which was that in Illinois, ordinary citizens could sue as citizens for a breach of the public trust doctrine if they could show that the transaction violated either the duties of loyalty or care. Preexisting precedent had taken the correct position that individual beneficiaries of a restrictive covenant—most notably Montgomery Ward and his friends—had standing to bring their own private action against the Park District for building in Grant Park in violation of a restrictive covenant in their favor. In that case, therefore, no public intervention was either needed or required. But Paepcke had no specially situated plaintiffs, so the Illinois Court was faced with a stark choice—to let either no person or every city resident bring that suit. A 1966 case, Droste v. Kerner, had embraced the first alternative, and was promptly overruled in Paepcke with this emphatic statement:

If the public trust doctrine is to have any meaning or vitality at all, the members of the public, at least taxpayers who are the beneficiaries of that trust, must have the right and standing to enforce it. To tell them that they must wait upon governmental action is often an effectual denial of the right for all time.

Once the suit was allowed, the question then was how the review should proceed. Paepcke stitched together several guidelines from two earlier Wisconsin cases, which “approved proposed diversions in the use of public trust lands” when public bodies controlled land open to the public and devoted to new public purpose only a “small” part of the whole area. Under the new project none of the “public uses of the original area would be destroyed or greatly impaired,” so that the losses to existing users were “negligible when compared to the greater convenience” of the rest of the public.

The term “diversions” was consciously used because the actual terms of the 1869 grant to the city of Chicago of Washington Park was categorical: the land was to be “held, managed and controlled . . . as a public park, for the recreation, health and benefit of the public, and free to all persons forever.” This imposed duties upon the Park District and its assignees to honor the terms of the trust. Those grant terms were exceedingly restrictive, so, in a classical maneuver of constitutional proportion, the Paepcke court gave a foot, but not a mile, when it found that this transaction met that six-part test for a proper exception to the terms of the 1869 grant. The OPC, however, could never meet this six-part test because it both flunks each element, and involves two additional circumstances adverse to the Foundation’s claim. First, the diversions are an unprecedented giveaway to a private party of public lands, and second, the massive alteration of a historical park is far more intrusive than the construction of a public school on a corner of Washington Park.

Thereafter the Paepcke Court summed up the situation by noting that there were tough choices that had to be made between keeping land in its “pristine purity” and allowing “encroach[ment] to some extent upon lands heretofore considered inviolate to change,” (italics added) under the 1869 grant. Paepcke’s closing passage rejects the notion that once a proposal has received a legislative blessing, the public trust doctrine becomes a nullity.

Such was the state of the precedents when this case first came before then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett in the initial run of the OPC case, who added a novel twist of her own. During the oral argument, the first question Judge Barrett asked both me and the defendants was whether the plaintiffs had standing to bring the case. That inquiry was perfectly sensible because every court has the duty to discuss, on its own initiative, if necessary, whether the case is properly before it. Due to the complex pattern of litigation, that standing issue had been resolved in favor of the plaintiffs in a prior case (argued by previous counsel) before the District Court Judge Blakey. But her decision was vulnerable on appeal because our public trust claim exclusively relied on an alleged general-citizen interest. It was therefore appropriate for Judge Barrett to dismiss those state claims on standing grounds. But since that procedural move was not a decision on the merits, the plaintiffs would be allowed to replead the case again if they cured the standing issue, as by pairing it with the federal claims under NEPA and the TA.

Nonetheless, Judge Barrett went badly off the rails when she got to her analysis of plaintiffs’ federal claims. At this point, she claimed that the plaintiffs have alleged “the deprivation of a property right,” without specifying what that property right was. She then went on to make the spectacularly incorrect argument:

Their argument disintegrates, however, when one reads more than the snippets they cite. Paepcke is particularly devastating: “in that case, the Illinois Supreme Court held that those owning land adjacent to or in the vicinity of a public park possess no private property right in having the parkland for a particular use. If adjacent landowners have no protected interest in public land, then the Plaintiffs don’t have one either. Although the Plaintiffs wish it were otherwise, the Illinois cases make clear that the public trust doctrine functions as a restraint on government action, not as an affirmative grant of property rights.”

Utter confusion. She was correct that if the plaintiffs had brought a neighbor claim, they would have had standing. But the plaintiffs never sued as adjacent landowners. Their sole claim was as city residents. As Judge Darrah had noted in 2016, Paepcke “held that each taxpayer of Illinois has a fractional beneficial interest in the property that the state of Illinois holds in trust for them, so as to create a protectable property interest—i.e., an affirmative grant. There were thus no grounds for her to enter an adverse judgment against the plaintiffs on the merits.

Since Judge Barrett’s actual decision only barred our federal claims, plaintiffs then did file their new state public trust doctrine claim before Judge Blakey, which he then dismissed on equally egregious grounds. His key maneuver was to splice together separate portions of Paepcke to make it appear that the only thing that matters is the “requisite legislative intent,” without once recognizing that the public trust doctrine has no “meaning and vitality” if clever legislative drafting can always block the constitutional challenge. Imagine if this view were applied to all cases involving freedom of speech and private property. The Constitution then could never restrain legislative action, however egregious. That will be the central issue before the Seventh Circuit on the current round of appeal.

3. The Financial Transaction

The third act in the OPC drama takes up where the public trust claim leaves off. More specifically, even if the basic deal between the city and the Foundation complied with that doctrine, the transaction still should have been set aside because the Obama Foundation has breached all the key terms of the Master Agreement with the city of May 19, 2019, when both the Foundation and the city wrongly claimed that all the terms of the deal were satisfied. Section 12 of the Agreement states the conditions precedent to the city’s obligation to close those transactions. These include:

Section 12(h): Construction Funds. The Foundation shall have submitted to the City a certification that the Foundation has received funds and/or gift pledge commitments in writing that in the aggregate equal or exceed the Projected Total Construction Costs of the Presidential Center.

Section 12 (j): Endowment. The Foundation shall have established an endowment having as its sole purpose paying, as and when necessary, the costs to operate, enhance and maintain the Presidential Center and the other Project Improvements during the term of the Use Agreement.

Section 13(c)(iv)): The Foundation is required at closing to provide “[a] certificate, executed by the Foundation, certifying that as of the Closing Date all of the representations and warranties of the Foundation contained herein are true and correct (with appropriate modifications or such representations and warranties to reflect any changes therein not known to the Foundation as of the Effective Date) or identifying any representation or warranty which is not, or no longer is, true and correct and explaining the state of facts giving rise to the change.”

The general conclusion of the Master Agreement states:

If any one of the above conditions is not satisfied by the Closing Date, the City may, at its option, waive such condition or, if the City does not waive such condition, the Closing Date shall be deemed postponed until such later date designated by the Foundation in a subsequent Closing Notice.

That last provision is strictly necessary because it would be utterly unworkable to let the Foundation breach any or all of these conditions and somehow be able to “cure” these defects sometime down the road, when no one knows how long the wait would be or what modifications would constitute a cure. The whole point here is that the transaction must be in order at the time of transfer to avoid forcing the city to take on extra risks of noncompletion. The standard contractual reference to “conditions precedent”—must be satisfied before further work could be done—is meant to block just that possibility.

Now look at the 2020–21 balance sheets of the Foundation by setting the costs of construction on the one side against the creation of the endowment on the other. Start with the Foundation’s 2020 Report (published in 2021), which listed a total endowment of some $560 million, of which some $70.5 million has been committed to pre-construction site-work already in the ground, and much to annual payroll, legal, accounting, and public relations expenses. Further dollars are committed to the many scholarship and public service programs of the Foundation. Of the residual assets, about $213.6 million was in cash (with net pledges of about $264.5 million available), with virtually no cash or pledges dedicated to either the Foundation’s construction or endowment programs. Also, as of March 12, 2021, the cost of construction was listed by the Foundation at $482 million, a figure that ballooned to over $700 million by June of 2021. In August 2021, just as the land transfer was completed, the Foundation announced that it needed $830 million to build the project and to operate the Foundation for its first year. But that statement did not mention that the Foundation also stated that it had to create a new endowment fund of some $470 million for maintenance, operations, and improvements. More recent developments revealed a pledge of $100 million for scholarships and similar programs from Airbnb, and another pledge of the same amount from Jeff Bezos to help train emerging leaders in the United States and around the world. But neither of these high-profile gifts were directed to the construction project, and none of these dollars were in any event placed in the Obama Foundation. In 2021, it was thus clear that the Foundation did not satisfy the condition precedents for closing the deal, which nonetheless was done on August 16, 2021.

Take first the construction costs. The Foundation observes that it had received $485 million in cash, which, as of March 12, 2021, was barely greater than the then-estimated (but unaudited) costs of construction of $482 million. But the receipt of the money is not the same as committing those funds exclusively to OPC project, and the plaintiffs protested by their letter of August 2021 that the deal only made sense if the Foundation kept the money in a separate account. How can the Foundation build the OPC if there is no cash on hand? The Foundation’s response is that they met the literal terms of the deal, to which our answer was that there are good faith obligations that have to be satisfied for the deal to make sense. Plaintiffs cited the 1917 New York case of Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon (1917) for the proposition that principles of good faith allowed for the implication of terms needed for the deal to make sense. The defendants belittled the reference of a New York case from over 100 years ago, without bothering to note that it has been cited favorably hundreds of times, and had been expressly adopted as Illinois law. Worse still, the defendants conceded that the costs had increased by over $200 million between that first report and the costs at the time of closing as of August 13, 2021. Valerie Jarrett, a close confidante of the Obamas and president of the Foundation, stated that the cost of “bricks and mortar” to build the complex “is a little less than $700 million.” But at no point did the Foundation provide, nor did the city request, any update of representations and warranties required by Section 13(c)(iv), which meant the deal could not have properly closed as of August 13, 2021.

The position of the Foundation and the city on the endowment clause was every bit as unsound. Their claim is that they satisfied the requirement by setting up an endowment account in June 2021 for $470 million, to which they then contributed $1 million, thus “satisfying” the original agreement’s call for a $470 million fund. Their position here, as with the costs of construction, is that they had “ample” time to make up the difference, thereby casting all the risk on the city if they fell short. Endowments are fully funded accounts, not promises to raise funds whose value is utterly uncertain. So those two verbal tricks allowed the Foundation and the city improperly to close, cutting down about 300 mature trees and breaking ground three days later, on August 16, 2021.

A substantial chunk of that ample time has passed, yet the Foundation’s overall financial situation only deteriorated in 2021. The most salient data in the 2021 990 tax return was the decline in moneys raised from $171 million to $159 million, or about 7 percent, even as inflation reached over 8 percent. Total assets were said to increase from $564 million to $694 million, but there was no explanation as to the source of that increase or what fraction of those funds were available to finish the preconstruction work, complete the building, and to fund the working endowment. The endowment had about $225 million in cash, and $242 million in pledges and grants receivable, roughly the same amount in total as the year before. The total annual expense budget remained at about $41 million. But in sharp contrast to the 2020 Report, the 2021 Annual Report devotes only a single page to finances, which in addition to the numbers mentioned above reports construction costs of close to $115 million, without mentioning either the total contract work, or the percentage of work completed for the moneys paid out. Yet it is incontrovertible that total construction costs had to increase owing to the combined impacts of inflation and supply chain difficulties. A 10 percent increase in overall project cost does not seem an unrealistic estimate, which would add well over $100 million to these accrued costs. The table of donors accompanying the report does not break out any gifts over the $1 million category; nor does it include the Bezos or AirBnB pledges. Beyond these bare essentials, the report is silent.

Given the financial condition, as of the August 2021 closing, the plaintiffs sought to amend their complaint to allege that both the city and the Foundation were in breach of the Master Agreement. It was evident that the plaintiffs were not parties of the Foundation-city contract, and thus these filings explained that we were suing in our capacity as citizens who have been wronged by the agreement. Illinois law explicitly allows these suits:

It is established that a taxpayer can enjoin the misuse of public funds, based upon taxpayers’ ownership of such funds and their liability to replenish the public treasury for the deficiency caused by misappropriation thereof. Consequently, a taxpayer has standing to bring suit, even in the absence of a statute, to enforce the equitable interest in public property which he claims is being illegally disposed of.

Within a day of filing the amended complaint, Judge Blakey dismissed on the ground that the Master Agreement (in Clause 34) did not allow persons who were not party to the contract to sue for its breach. But our amended complaint never alleged such a theory. Yet Judge Blakey held, without citation, that it had alleged only that theory and thus dismissed the entire case for lack of standing, and, taking a page from Judge Barrett’s playbook, by rejecting a claim never brought and ignoring the case that was filed. The upshot of that outright blunder is that the plaintiffs have been denied discovery for months on this vital claim and they will be until that judgment is reversed (if at all) on appeal. The Foundation’s finances thus remain to this day concealed from view.

At this point, Judge Blakey’s procedural acumen took hold. Plaintiffs can only appeal as of right once the entire case has been resolved on all issues. Otherwise, the District Court judge has full discretion on whether to allow the appeal under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 54(b). Predictably, when asked, he denied the plaintiffs’ request for an expedited appeal, even though the legal issues on the environmental issue were wholly separable from those on the public trust and the improper transfers. At present the entire case is on appeal on all issues, but it is unclear when the briefing will be completed or when the Seventh Circuit will issue its opinion, after which the three different portions of the case may be brought before the Supreme Court.

Conclusion

So I shall end with this sobering note. Before I was asked to work (pro bono, I might add) for the plaintiffs, I was told by more than one wise person that it is legal suicide to litigate against the Obamas in Chicago. Thus far they have been proven all too correct by rulings, tactics and maneuvers that I never thought possible. Let’s hope with the upcoming rounds of litigation that our various charges will receive a more balanced and accurate deliberation, from which the plaintiffs have absolutely nothing to fear.

About the Author

Richard A. Epstein is a Laurence A. Tisch Professor of Law, The New York University School of Law; the Peter and Kirsten Bedford Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution; and a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School. He has been pro bono lawyer for the plaintiffs on the case since 2019. My thanks to Matthew Philipps, Matthew Rittman, and Elle Rogers of the University of Chicago, Class of 2023, and to Ben Chesler, Will Lanier and David Leynov, NYU law school, class of 2024 for their insightful and excellent research assistance.