"When I use a word...it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less."--Humpty Dumpty

"The question is whether you can make words ean so many different things."--Alice

From Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass

Introduction

You are about to take a journey into a world of contradictions—a place where Introduction things are not always as they appear, and where words do not always mean what they should. No, we’re not taking a trip to Alice’s Wonderland, we’re going to explore . . . the federal budget process.

As we are about to discover, what a word means to the government isn’t necessarily what it means to the rest of the world. But this is not just benign bureaucratic lingo—it is a massive tool of deception. It’s also one of the reasons the budget deficit continues to expand, all amidst claims of sacrifice and “making the tough decisions.”

In 1974, politicians dreamed up the ultimate tool: they figured out a way to spend all the money they want, but yet be able to look their voters in the eyes and say “we’ve cut spending.” That ultimate weapon is called Current Services Budgeting.

What is Current Services Budgeting?

Despite Americans’ concerns about high taxes and the deficit, the federal budget and the national debt continue to expand. Yet every year we hear politicians boldly claim that they are cutting spending. Unfortunately for the taxpayer, the term “cut” has a very different meaning in the world of politics than it does in the real world of mortgage payments and college tuition. When politicians claim to be cutting spending, what they really mean is that they merely will be increasing spending a little less than they had originally planned.

In the halls of Congress, this misleading phenomenon stems from the 1974 decision to require the annual production of a “current services budget.” The current services budget provides an estimate of how much spending will be needed in the coming year to provide the same level of government services provided in the previous year. Those estimates serve as an inflated “baseline” from which claims of cuts in spending are made. For example, say a program received $100 million last year and the current services estimate for the coming year is $106 million. If Congress votes to spend only $104 million, they will call it a $2 million cut, when in reality the American taxpayers will be forced to ante up $4 million more for that program than they did the year before.

In a nutshell, because of current services budgeting, when politicians claim they are cutting spending, they don’t necessarily mean that they will be spending less than the year before. This has created a fundamentally dishonest system which has defrauded the American taxpayer of billions of dollars.

-

Since current services budgeting was implemented, real annual discretionary spending growth has tripled.

-

If spending growth had not increased, the federal budget would have been $60 billion smaller in FY 1994, or $231 less per person.

-

During this same period, Americans have seen their real annual income growth slow by nearly half.

-

While current services budgeting has provided each and every program with an automatic “cost of living” adjustment, American taxpayers have seen their incomes barely keep pace with the growth of inflation.

History of Current Services Budgeting

Current services budgeting came about in the early 1970s as one part of a larger package of reforms, the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. After several consecutive years of budget deficits, those reforms were adopted in a effort to make it easier for Congress to balance the budget. One way Congress felt that could be done, given the growing complexity and size of the budget, was to have at their disposal each year an objective measure of how much it would cost to provide the same level of government in future years. It was believed that this would make it easier for Congress to assess the impact of changes they considered.

To that end, the 1974 Budget Act required the President’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to present, along with their annual budget proposal, a “current services” budget. The current services budget would provide estimates of the expenditures necessary to continue programs at “the same level as the current year without a change in policy.”1 (In general, this involved an adjustment for expected inflation and in some cases for things such as changes in demographics).

First implemented in fiscal year 1976, these current services estimates soon became the “baseline” of choice. Thus, in Congress’ annual budget deliberations, instead of comparing proposed levels of spending to what was spent in the previous year, politicians could compare their proposals to the inflated current services estimates. In essence, the current services baseline has become an inflated "straw man" against which spending increases can be favorably compared. The result of this change has been a perennial plethora of phantom budget “cuts” that are actually not cuts at all. This phenomenon works to the advantage of both the opponents and proponents of increased spending.

As the previous hypothetical example indicates, current services budgeting enables politicians to deceive the American taxpayer by claiming that spending is being cut, when in fact it is increasing. Such misleading debate takes place every year, as illustrated by these recent real-life examples.

Congress' Proposed "Cuts" in the School Lunch Program

The House Republicans’ welfare reform proposal provides a timely example of the deceptiveness of current services budgeting. The proposal includes a provision to replace the federal school lunch and breakfast programs with a block grant to the states, and a provision to limit the rate of growth in that funding. Opponents have called the proposal a cruel and heartless spending "cut," and an attack on defenseless children. Rep. Dick Gephardt (D-MO), the House Minority Leader, protested the proposal, saying ". . . it is immoral to take food from the mouths of our children . . ."2 Even citizens who generally support cuts in government spending reacted to the news of "cuts" in the school lunch program with mixed emotions, wondering aloud whether this was among the most necessary of spending cuts.

Despite opponents claims to the contrary, the welfare reform proposal calls for a spending increase of 4.5 percent on the school lunch program in FY1996 over FY1995. How can opponents claim that a 4.5 percent increase is a cut? Because that 4.5% increase is smaller than the 5.2% increase proposed by the Clinton Administration. So while spending would continue to rise—by an additional 18 percent from FY1996 to FY2000—because of current services budgeting, politicians can make political hay out of claiming that it is being cut.

The furor over the school lunch program only underlines the insidious way current services budgeting allows politicians to spin budgetary issues to suit their political purposes. In the meantime, accuracy and truth are the first victims of the budget process, and citizens are purposely misled.

President Clinton's FY 1996 Budget Proposal

At a recent news conference announcing his $1.6 trillion budget proposal for FY 1996, President Clinton stated, “My budget cuts spending, cuts taxes, cuts the deficit.”3 Most Americans would likely conclude from such a bold claim that the spending, revenue, and deficit figures being proposed for FY 1996 were lower than those for the previous year (FY 1995). However, one must turn no further than page 2 of the President’s mammoth budget document to learn the truth. In spite of its claims, in FY 1996, the President’s budget proposes to:

- Increase spending by $73.2 billion.

- Raise revenue by $69.1 billion.

- And allow the deficit to rise by $4.2 billion.

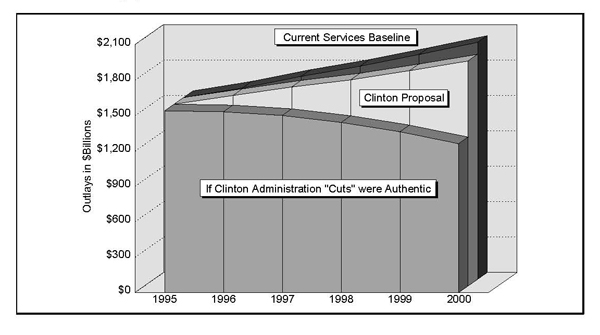

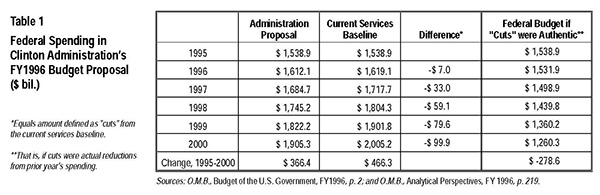

As Table 1 shows, while the President claims that his proposal would cut spending, it would actually increase spending by $366.4 billion over the next five years, pushing the budget over the $1.9 trillion mark by the year 2000.

Only by comparison to the current services baseline (see Figure 1) can the President’s proposal of a $366 billion spending increase be labeled a cut. If each year’s "cuts" from the current services baseline were instead actual reductions from the prior year’s budget, by the year 2000 the budget would have declined by $280 billion, falling below $1.3 trillion for the first time since 1990. As a result, if the President’s "cuts" were genuine spending reductions, that FY 2000 budget would be $645 billion smaller than his own numbers say it will be. That amounts to a potential savings of more than $2,300 per capita in FY 2000 alone that America’s overburdened taxpayers will be denied.

Figure 1:

The Stealth Budget Cuts in the Administration's FY 1996 Budget Proposal

President Clinton's FY 1994 Deficit Reduction Plan

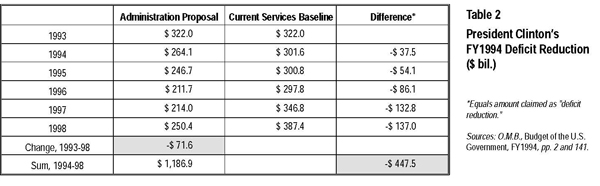

In 1993, President Clinton’s much heralded “deficit reduction plan”—his FY 1994 budget—provided another example of how current services budgeting deceives the public. Speaking on the President’s proposal, White House Budget Director Leon Panetta claimed, “we’re looking at $514 billion in deficit reduction.”

As with the President’s recent FY 1996 budget proposal, the numbers on page 2 of the FY 1994 document clearly disproved those claims. By FY 1998 the deficit would have declined by less than $72 billion. Table 2 shows how this $72 billion decrease was magically transformed into a "$514 billion reduction." Each year’s deficit projection in President Clinton’s proposal was smaller than the deficit projection in the current services budget. The sum of each of those “cuts” is $447.5 billion. That figure, combined with the anticipated effect of other actions taken by Congress earlier that year, was the basis for Panetta’s claim of a $514 billion reduction in the deficit. As a result, because of the utilization of current services budgeting, though the deficit would decline by only $72 billion, the Administration claimed that it was being reduced by more than $500 billion. Furthermore, since the budget would remain unbalanced, nearly $1.2 trillion would be added to the national debt by FY 1998.

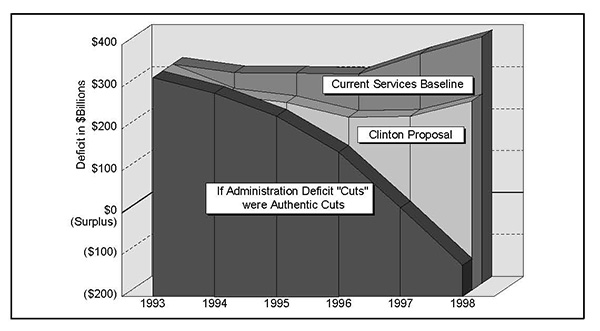

In contrast, as Figure 2 illustrates, if the $447.5 billion in phantom cuts from the current services baseline were instead actual reductions from the prior year’s deficit, by the year 1998 there would actually be a substantial budget surplus of $125.5 billion. Instead, even President Clinton’s own numbers predicted that the deficit would begin to grow larger again after FY 1996.

Figure 2

The Phantom Deficit Cuts in President Clinton's FY 1994 Budget Proposal

Reagan's "Draconian Cuts" in Social Spending

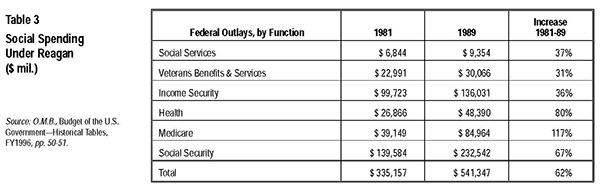

Each year that President Reagan presented his budget proposal to Congress, that proposal was declared “dead on arrival,” in part because opponents claimed that the proposal called for dramatic cuts in social spending. Of course, those “cuts” were not what American taxpayers normally would think of as cuts. Instead they were actually increases, albeit smaller increases than those contained in the current services budget. Nevertheless, the constant protests about the Reagan “cuts” helped create a lingering perception that the Reagan administration made drastic cuts in social spending. As Table 3 shows, despite the claims to the contrary, social spending rose substantially under Reagan, increasing by 62 percent from FY 1981 to FY 1989.

How Current Services Budgeting Helps Continue to Fund Outdated Programs

In addition to injecting dishonesty into the annual budget debate, current services budgeting has also helped to maintain the existence of outdated programs. The current services estimates assume that all programs are to continue to function at “the same level as the current year without a change in policy.”7 Essentially, Congress has codified the assumption that each and every program will continue to receive funding, and has as much as put government spending on autopilot. As a result, it is far more difficult to terminate programs that have completed their missions or outlived their usefulness. While such programs are frequent targets of the budget ax, they inevitably escape cuts, in part because their proponents do not have to argue for their continued existence.

For example, the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) was established in 1935 to bring electricity and telephone service to rural America. As former REA director Harold Hunter once said, REA’s work “was done a long, long, long time ago.” Despite that more than 98 percent of all rural homes now have access to electric and phone service, the REA lives on, distorting the credit markets by providing $2 billion a year in below market rate loans to rural electric coops.

Another obsolete agency is the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). ICC was established in 1887 to regulate the budding railroad industry, but later was given domain over the interstate trucking and bus industries as well. Since 1980 all three of ICC’s industries have been largely deregulated, making the ICC an agency with virtually no mission. Nevertheless, it has yet to be put out to pasture.

Yet another example is the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). The ARC was established in 1965 in an effort to relieve the poverty and isolation of the Appalachian region through highway construction and social programs. While these problems have largely been alleviated, the ARC lives on. President Clinton has proposed over $200 million in federal outlays for for the ARC in FY1996. Recently it was announced that among ARC’s grants is $1.25 million to go towards the construction of a new football stadium that the NFL’s new Carolina Panthers will use as a summer practice facility. The 8,000 seat stadium will be owned by Wofford College, a private liberal arts college in Spartanburg, South Carolina, but will be paid for by taxpayers.11

Programs like the REA, ICC, and ARC, that have clearly completed their missions or outlived their usefulness are in abundance throughout the federal budget. It is current services budgeting, in part, that keeps them alive.

Has Current Services Budgeting Contributred to the Rapid Growth of Government?

As the preceding sections have discussed, current services budgeting has injected dishonesty into the budgetary debate by allowing politicians to claim that they are cutting spending when in reality they are doing just the opposite. In addition, current services budgeting has made it more difficult to terminate programs that have outlived their usefulness. The end result is that current services budgeting creates a pro-spending bias that makes it more difficult for budget growth to be restrained.

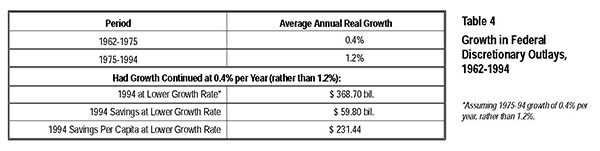

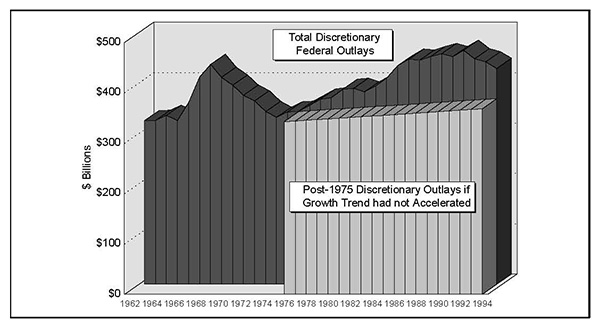

Table 4 shows how this pro-spending bias has coincided with an acceleration in the growth of the federal budget. From 1962 to 1975, federal discretionary spending12 grew by $16.8 billion (after adjusting for inflation), or at an average rate of 0.4 percent per year. Since then—after the first current services budget was presented in 1976—that growth rate has tripled. From 1975 to 1994, real federal discretionary spending grew by $86.7 billion, an average rate of 1.2 percent per year. Figure 3 illustrates how that accelerated budget growth has affected the size of the federal budget.

-

Leading up to the adoption of current services budgeting (1962-75), federal discretionary spending grew at a rate of 0.4 percent per year (after adjusting for inflation).

-

Since then that growth rate has tripled, rising to 1.2 percent per year.

-

If real discretionary spending had not accelerated, the budget would have been $60 billion smaller in 1994.

-

The taxpayer savings in 1994 alone would have amounted to $231 per capita.

Figure 3

Acceleration of Discretionary Spending Growth Since Current Services Budgeting

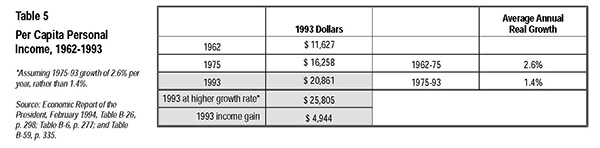

Incidentally, while the federal budget was experiencing unchecked growth—in part due to current services budgeting—Americans saw their incomes do just the opposite. As Table 5 and Figure 4 shows:

-

The real growth of per capita income slowed from 2.6 percent per year to 1.4 percent per year after the implementation of current services budgeting.

-

If income growth had not slowed, per capita income in 1993 would have been nearly $5,000 (or 24 percent) higher.

So while American workers have been deprived of adjustments to their cost of living, all government programs routinely get such adjustments.

Figure 4

Per Capita Personal Income Growth Has Slowed Since Current Services Budgeting

Out-of-Touch Federal Government

Current services budgeting is just one of the many examples of how Washington is out-of-touch with the American people. America’s families have no choice but to be conscious of how much income they are earning, and must plan their spending accordingly. There are many things they would like to do that they cannot afford to do, and neither their incomes nor their discretionary spending get automatic cost of living adjustments. They must set priorities as to how their limited resources will be spent. But through current services budgeting, our federal government does just the opposite.

Rather than accepting that there are limits to how much money should be taken from American workers, taking a hard look at where the taxpayers’ money is being spent, and setting clear priorities as to which programs should be continued and which will be terminated, politicians assume that each and every program will continue to be funded. On top of that, each program is given a “cost of living” adjustment. Then, after complaining about the “tough choices” they have had to make, our friends in Washington go about the business of figuring out how to pay for their profligate ways.

Unlike America’s families, for whom there is a distinct limit as to how much they can borrow, the federal government’s range of options includes a virtually unlimited ability to borrow. Further, while America’s families can typically borrow only to finance a home, a car, or their children’s educations, the federal government can borrow just to pay its everyday expenses. Because of this unchecked ability to borrow, it now takes 40 cents of every dollar collected from the personal income tax just to pay the interest on the national debt.

If an American family or business chose to run its budget the way Washington does, they would soon be thrown in jail. In real life, as contrasted with the Wonderland of Washington, DC, an employee who continually fails to meet expectations is fired, not given a raise. And if a family or business has an unexpected decline in income, they find ways to cut back. Sometimes they cut back on entirely worthy, desirable budget items. But they have to live within their means. Individuals, families, businesses, taxpayers—all have to live within their means. Only the government can continue to live beyond its means, at the expense of those same individuals, families, businesses and taxpayers.

Returning to Truth in Budgeting

Despite constant claims to the contrary, Congress has yet to take serious steps to rein in the growth of government by cutting spending. In fact, the overall budget has not been cut since 1965, when spending declined by $300 million from its 1964 level, and even that cut came only after what was then a huge $7.2 billion spending increase in the previous year (1964).

In order to restore honesty to the federal budget process, the practice of current services baseline budgeting must be abolished. This would make it easier for reporters and everyday citizens to see through politicians’ deceptive claims of spending cuts. This would also remove the pro-spending bias from the budget process and make it easier to eliminate programs that have outlived their usefulness.

Conclusion

What is the solution? In order to help slow (if not reverse) the growth of government and return honesty to the federal budget process, Congress should put an end to the annual deception created by current services budgeting.

-

Congress should immediately discontinue the practice of current services baseline budgeting.

-

Congress should, instead, begin using a zero-baseline budget process, requiring every program to stand on its own merit each year.

-

Congress should follow the lead of many state governments and pass sunset legislation which would provide for the automatic termination of all programs and regulations after five years unless Congress votes specifically to continue them.

Because of current services budgeting, the federal budget process is fundamentally dishonest. The American taxpayers deserve to be dealt with honestly, rather than being deceived by their elected representatives. Discontinuing the practice of current services baseline budgeting would begin to restore honesty to the federal budget process. Furthermore, along with implementing a zero baseline budget process and enacting sunset legislation, this would make it easier for those politicians who are serious about cutting spending to comply with the voters demands for a smaller, less intrusive, and less expensive government.