Social Security is in serious financial trouble, and will be unable to pay its full obligations in less than 20 years. Some Republicans are proposing reforms that would prolong the financial slide but do nothing to change the program’s underlying dynamics. Some Democrats are irresponsibly proposing actually increasing benefits.

In 2005, Congress considered transitioning Social Security to a system of prefunded personal retirement accounts. But the Bush administration did such a bad job of selling the reform, and Democrats did such a good job of attacking it, that it fell apart.

But we don’t have to get to reform all at once. We can start with two important parts of the program: disability and survivorship.

Social Security Isn’t Just About Retirement

Social Security is actually three separate but related programs. First, it provides a small income stream for every senior who contributed the required 40 quarters to qualify. Second, there is a disability insurance provision that covers those who become disabled. And third, it has a survivorship provision that primarily helps a qualified deceased worker’s spouse or minor children.

How Social Security Is Divided

Currently, workers’ 12.4 percent FICA payroll tax goes to the Social Security Trust Fund, which is divided between the old age and survivors portion (10.6 percentage points), known as the OASI Trust Fund and disability insurance (1.8 percentage points), or the DI Fund. While neither is doing well, the disability insurance trust fund is in worse financial shape.

Social Security’s Disability Program

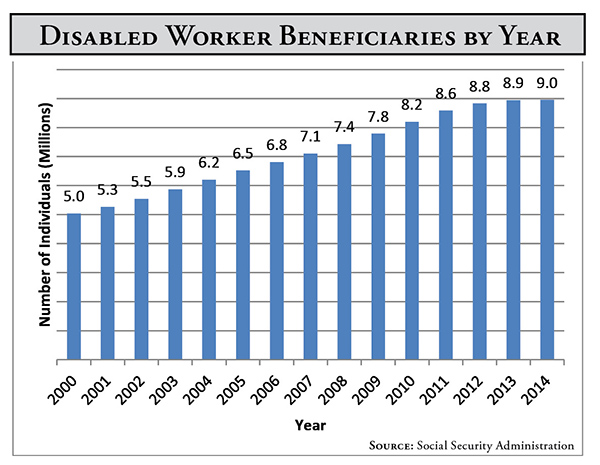

Disabled beneficiaries have grown nearly 40 percent over a decade, to nearly 9 million. The Social Security trustees warn, "Lawmakers need to act soon to avoid automatic reductions [by 20 percent] in payments to DI beneficiaries in late 2016." The stopgap solution has been to take money from the OASI fund to cover DI shortfalls.

The policy question is why disability insurance is part of the Social Security system in the first place. The private sector could easily handle this function, removing the government middleman. And we know that because it’s been done.

How Texas Provides a Model for Reform

In 1981-2, three Texas counties (Galveston, Matagorda and Brazoria) opted out of Social Security and created an alternative, personally owned retirement program that mirrored all three of Social Security’s primary functions—except the benefits are better. It’s known as the Alternate Plan. Today, only those state and local pension funds that never participated in Social Security can take this option without congressional action.

Under the Alternate Plan, county employees and their employer still pay the same as the FICA payroll tax, but a portion of it goes toward a private sector disability insurance policy.

Disability Benefits

In 1999 the Government Accountability Office compared disability benefits under the private sector Alternate Plan and Social Security’s disability insurance (SSDI) program. Under the Alternate Plan employees are immediately eligible to receive disability insurance; while workers participating in Social Security and over the age of 30 must work 20 of the previous 40 quarters (i.e., five years) to be eligible for disability insurance.

In addition, the GAO found that a low-income disabled worker in 1999 would receive nearly twice as much under the Alternate Plan as under Social Security. And a higher-income worker would receive more than twice the SSDI amount.

The Alternate Plan’s disability benefit is based on the worker’s salary. Today, disabled workers receive between 66 percent and 80 percent of their monthly salary, up to a maximum of $8,000 a month, according to the Plan’s financial manager. Under SSDI, the large majority receives less than $1,700 a month, and only a handful receives more than $2,800.

In short, disabled people are much better off under the Alternate Plan. But so is the country because private sector companies would be monitoring those receiving benefits to ensure (1) they actually are disabled and (2) whether they have improved and could return to work—both sources of significant potential fraud in the current system.

Survivorship Provision

The Alternate Plan also replaces Social Security’s survivorship provision with a private sector life insurance policy. If a worker dies, the family or estate is paid the proceeds, equal to four times the employee’s salary up to $215,000—quite a bit better than Social Security’s $255 death benefit.

Of course, the government would be paying more if there were a surviving spouse who had not personally qualified for Social Security benefits, but under the Alternate Plan every deceased employee’s family (or estate) gets the life insurance.

The Disability Policy’s Cost

Those in the Alternate Plan pay between 2.5 and 4 percentage points of their 12.4 percent FICA contribution for their private sector disability and life insurance (the specific amount can vary slightly from year to year based on the number of people on disability). The rest of their contribution goes to a professionally managed, personal retirement account that has always provided positive returns, even during the recessions.

An Insurance Solution, Not Investment

Privatizing Social Security’s disability insurance and survivorship benefits doesn’t depend on people making good investments. Workers could choose from a number of qualified disability and life insurers, and a portion of their payroll tax would go to the insurers rather than the government. Democrats who supported Obamacare will find it difficult to argue that we cannot allow taxpayers’ dollars to go to private sector insurers. Nor can they argue it’s a risky scheme since three Texas counties have been doing it for nearly 35 years.

Transition Costs

One of the major challenges in transitioning to personal retirement accounts is funding the transition costs. Social Security currently faces about $13.4 trillion in unfunded liabilities, money it is obligated to pay above expected revenues. If workers began diverting their payroll taxes to a personal retirement account, there would be no money to fund current retirees.

But, disability and survivorship are different, because the money comes from current workers and goes mostly to current workers.

Current workers would choose among qualified disability and life insurers. Their disability and survivorship portions of their payroll taxes would then be transferred to the insurers. Probably the best way to cover those currently on disability benefits would be to require insurers that choose to participate to accept them as well—just as Obamacare required health insurers to accept applicants regardless of their health status. However, insurers would be allowed to challenge a person’s claim if it were obvious the person was no longer disabled, which could shrink the disability rolls.

Conclusion

The best way to solve Social Security’s long-term financial challenges is to privatize all of its components. However, critics have long resisted that solution for the income security portion, arguing that the stock market is too volatile and that workers can’t be trusted to make good investment decisions.

But disability and survivorship doesn’t require investing, just choosing an insurer. These two changes won’t solve all of Social Security’s financial problems, but they would be a good start.